When the Ingle family moved to Toronto around 1901, Bertha's opportunities to develop her art through formal study expanded.

By then in her early twenties, she had certainly become an artist, had won prizes for her pictures, in Owen Sound, and knew it was her true vocation. We believe she likely had art lessons in Owen Sound from an Ontario-born American artist who had a studio there, Harry Valentine Woodhouse.

But Toronto offered more. Within a short time, she became a student of Farquhar McGillivray Knowles, a renowned artist and teacher as well as a prominent and important figure in the art world and in Toronto society. Within a few years, Bertha had become an associate of the Knowles studio, and had taken on teaching assignments of her own in the Westbourne School for Girls, where McGillivray Knowles was Art Director. Naturally we were curious to find out where the Westbourne School and the Knowles studio were located, and what they were like.

It happened that at about that time, a long-time close friend (and staunch pillar of the Genealogical Research community hereabouts) suggested we might be interested in a course that was being given regularly, twice a year, in the University of Toronto's School of Continuing Studies. It was called Your City, Your House, Your Family. It was taught by James F S Thomson, and is still being offered as Toronto's Past: Your City, Your House, Your Family.

It was a revelation! Advertised as a course in the resources and methods for doing research into genealogy and the history of buildings and neighbourhoods, it is in fact much more than that. In both its underlying philosophy and its practical applications, it emphasizes the interconnectedness of all these areas of investigation. We learned (and saw first hand, right away) how a broad enquiry that encompasses people, structures, and neighbourhoods can be much richer than a narrower search into any one of these. Pursuing all these aspects, following the tangents and the curiosities, almost always turns up unexpected insights and delights. James Thomson goes above-and-beyond in helping students get started on their specific personal research interests, using their personal projects as the practical illustrations for the class.

My sister proposed our questions about the Westbourne School and the Knowles studio as an illustrative enquiry for the course:

The Ingle family moved from Owen Sound to Toronto around 1901, and Bertha is said (in her obituary) to have studied with Farquhar McGillivray Knowles, RCA, and become an Associate of his studio. We know from a photograph that she did some teaching at Westbourne School on Bloor Street West. There is some information about Mr. and Mrs. Knowles and their studio at

http://www.goldiproductions.com/thecanadasite/art/art20_knowles.html

http://www.mayberryfineart.com/artist/f_mcgillivray_knowles

The obituary of Mr. Knowles says: "For many years the Knowles studio on Bloor St. West, converted from a luxurious stable of an earlier day, was a Saturday night rendezvous for lovers of painting, music and literature. When Mr. and Mrs. Knowles removed to New York in 1915 they were banqueted by a party of hundreds of Toronto friends."

I have found that in the 1911 census, Mr. and Mrs. Knowles were listed in a "house" at 340 Bloor Street West, and the Westbourne School, principal Margery Curlette, was also at 340 Bloor Street West. Later in the Toronto Blue Book for 1913, Mr. and Mrs. Knowles were at 278 Bloor Street West, and so was the Westbourne School.

We'd be interested in the history of this property or properties, and in where the studio was.

We soon learned that not only were streets frequently re-named in Toronto's early history, but the properties on them were sometimes re-numbered, and not necessarily in systematic ways. James Thomson was able to help us establish that the numbering on the north (even-numbered) side of Bloor Street West was changed some time in the early 1910s, so the addresses 340 and 278 Bloor Street applied, in fact, to the same property at different times. And in so doing, he pointed us to several amazingly useful resources, one of which was the Fire Insurance Plans of the City*, which are gratifyingly detailed plans of buildings and other urban features. On Sheet 386 of the Fire Insurance Plans, 1914 - 1918 (found in the microfilm collection at York University's Scott Library), we can see that the studio was located behind a larger building, the Westbourne School, by then re-numbered from 340 to 278 Bloor Street West. Zoom in to the lower right-hand corner.

The School building itself was a formidable structure. There are photos of it in Toronto Society Blue Book Directories advertisements, for example in 1908 and 1913. The photos in those two ads show glimpses of the Knowles studio, behind the main building. Below is another early ad, the photo taken from a different angle:

My sister recognized that Jack Batten had included a photo of this very house in his book on The Annex (it appears at the start of chapter 3, and also in a cropped form on the cover), observing that it was one of the earliest in Toronto designed by renowned architect E J Lennox, who also designed Toronto's Old City Hall, Casa Loma for Sir Henry Pellatt, and many other notable Toronto landmarks.

Searching the Toronto City Directories, my sister also established that the property was occupied by James Crowther in 1897; by the Westbourne School and the Knowles Studio in 1914; and by James Crowther again in 1917 (with 'Havergal Preparatory' at the rear). We think Mr Crowther must have been the owner throughout this period, leasing it to the School and to McGillivray Knowles for several years.

Sadly (many would say), the E J Lennox-designed house at 278 Bloor Street West has been demolished, long ago. We hope to find evidence of when exactly that was. Tantalizingly, it has occurred to us that the house may still have been standing when my sister and I were students in the area nearby in the early 1960s, in which case we would have walked past it hundreds of times. How disappointed we are that at that time we didn't know enough to look for it. Note to all younger potential family historians: Start Now!

* And Another Thing ...

I mentioned tangents! The same Fire Insurance Plans elucidated something I'd been interested in for quite a while, namely the exact location and configuration of the baseball stadium at Hanlan's Point on the Toronto Islands. It was there on September 5th of 1914 that Babe Ruth hit his first home run as a professional baseball player (at least, in a game that counted), and also, incidentally, pitched a one-hitter for the Providence Grays against the Toronto Maple Leafs of the Triple-A International League. Those are the facts.

But there are always legends, as well, where the Babe is concerned. One legend has it that the home run ball splashed into Lake Ontario (which many people believe was practically lapping at the back of the right field wall) and that the ball may still be there. Another says the ball was actually discovered in the water in the 1960s and eventually put on display; and that it was then stolen by a baseball purist who ran away and threw it back into the Lake, "where it belongs".

As much as I would love to believe the story, it's almost surely poppycock. The 1914 - 1918 Fire Insurance Plan, sheet 178A, along with a photo of that part of the ball park I recently discovered, taken from the City of Toronto Archives, show that beyond the right field fence were:

As much as I would love to believe the story, it's almost surely poppycock. The 1914 - 1918 Fire Insurance Plan, sheet 178A, along with a photo of that part of the ball park I recently discovered, taken from the City of Toronto Archives, show that beyond the right field fence were:

- quite a few rows of open spectator seats;

- a covered structure called the Old Mill amusement ride;

- a roller coaster structure built of wooden trestlework (both these rides part of the Hanlan's Point Amusement Park); and

- a walkway complete with row of trees.

It would have taken a truly prodigious blast, perhaps of 400 feet or more, to clear all that and find water, a highly improbable feat in the 'dead ball era'. If it had actually been done, the news reports of the game would surely have said so, but as far as I know, none do.

Veteran sportswriter Lou Cauz has reportedly said that he once talked to an elderly retired clergyman, then in his 90s, who told Lou he was in the right field seats that day, and that's where Babe's homer landed.

Inevitably, however, the legend persists! Some of the folks who believe it also say Babe hit another home run into Lake Ontario in 1930, from Maple Leaf Stadium (which was at the foot of Bathurst Street). This is even crazier. The nearest water, beyond the straightaway centre field fence, was the Western Gap, easily 650 feet or more from home plate.

Inevitably, however, the legend persists! Some of the folks who believe it also say Babe hit another home run into Lake Ontario in 1930, from Maple Leaf Stadium (which was at the foot of Bathurst Street). This is even crazier. The nearest water, beyond the straightaway centre field fence, was the Western Gap, easily 650 feet or more from home plate.

In the photo, Maple Leaf Stadium is in the left foreground, and Hanlan's Point Stadium can be seen, too, way off in the distance.

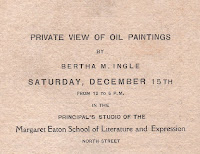

It was probably in 1906 that Bertha May Ingle presented a 'private view' of oil paintings in the Principal's Studio of the Margaret Eaton School of Literature and Expression. We have the invitation card and catalogue, giving the date as Saturday December 15th (without a year). The catalogue lists twenty paintings by title and price.

It was probably in 1906 that Bertha May Ingle presented a 'private view' of oil paintings in the Principal's Studio of the Margaret Eaton School of Literature and Expression. We have the invitation card and catalogue, giving the date as Saturday December 15th (without a year). The catalogue lists twenty paintings by title and price.